In the mid 90’s I found myself in a very precarious position: the husband in a married team of new parents, unexpectedly locked out of their business by their silent partners for suspicion of embezzlement.

While this presents a story all on its own, suffice it to say that our business partner’s accusations were eventually discovered to be unfounded (the butler did it) but the damage was done and, in the meantime, I needed work!

With a bright, pink, new baby at home, it was up to me to keep the money coming in – and fast! I applied at numerous places and – *gasp* – even cut my hair to take a position at one of those warehouse club places.

I hated the job, which entailed doing all the menial, goofy tasks your first-time, teenage employee would do: fetching carts, collecting empty cartons from shelves, manning the hot dog stand, bagging orders, etc. But I was doing the job at the age of 26 and after having owned my own business! It was especially pleasant for me when someone I knew came through the line. My favorite was the acquaintance (who, as it turns out, was the aforementioned butler before he was caught!) came up to me and said: “Well, look at how far you’ve risen.” Nice.

It was better than no job at all, though, and I was thankful to have it.

Still, I kept my eyes open for another job and, when a friend suggested I apply at his place of work, I jumped at the opportunity. The next thing I knew, I was filling out an application to work at a bronze-art foundry.

In the 1980’s, my hometown of Loveland, Colorado had decided to revitalize itself by becoming a center of bronze-art casting. It was a strange decision, seemingly out of the blue but better than deciding to remain a center of regional derision, I suppose. For the most part, the gambit worked. By the time I was knocking on the industry’s door for a job, there were three major foundries in town and numerous smaller studios offering full or partial casting services.

The position I was applying for was “wax-spruer” and, well, I suppose I’d better explain the process a bit so you wont think I’m just spruing with you.

We used the “lost wax” process to cast bronze. A process with a number of reasonably simple but somewhat repetitive steps:

#1- Someone sculpts a happy, prancing pony or a gawping, large-eyed child (alternately they can sculpt something interesting that *wont* sell to the modern, discerning public) using whatever materials they wish: clay, foam, wood, wax, hamburger, wadded up art degrees, etc.

#2- Said sculpture is then molded, a process involving figuring out where the piece may need to be cut, where the halves of the mold will split, and adding any “gates” to allow for an easier flow of wax or metal when pouring. The mold is made by brushing on many layers of latex rubber, finished off by a thick coating of plaster, not unlike a cast you might wear after breaking a bone while working in a bronze art foundry.

#3- The original sculpture materials are often damaged during the molding process and discarded. The mold, however, proceeds to the wax pour room where hapless individuals wrestle it over vats of hot, liquid wax, carefully pouring in and allowing to cool layer after layer of hot wax until it builds up to a thickness strong enough to be pulled from the mold – around a sixteenth to a quarter of an inch thick.

#4- The resulting wax copy of the sculpture is now “chased,” meaning the removal of any imperfections and seam lines. There may also be reconstruction or final sculpting tweaks (either by the artist themselves or by the just-above minimum-wage chaser in case the celebrated artist wants to improve their work – I wish I was joking here).

#5- Once the chase job has been approved by the artist, the finished wax is transported to the spruer who hacks it back into pieces once again and attaches said pieces to large cups and bars of wax, using wax “gates,” to allow not only for maximum metal flow but also survival of the shell process.

#5- Once the chase job has been approved by the artist, the finished wax is transported to the spruer who hacks it back into pieces once again and attaches said pieces to large cups and bars of wax, using wax “gates,” to allow not only for maximum metal flow but also survival of the shell process.

#6- The sprued items are now ready for shell: another layer-by-layer process involving various slurries and sand which are built up to provide a thick, heat resistant, ceramic shell. The process is one of the more difficult as the shell makes the pieces progressively more heavy and challenges the integrity of the sprue bonds. The shell crew, like wax pourers, are the unsung heroes of the foundry.

#6- The sprued items are now ready for shell: another layer-by-layer process involving various slurries and sand which are built up to provide a thick, heat resistant, ceramic shell. The process is one of the more difficult as the shell makes the pieces progressively more heavy and challenges the integrity of the sprue bonds. The shell crew, like wax pourers, are the unsung heroes of the foundry.

#7- After curing, the shelled waxes are put in a large autoclave in order to melt out the victory brown wax – that’s the “lost wax” part of the process. Only, the wax is not lost. It is collected, cleaned, and reused over and over, with only a small portion of it being truly “lost” in the process.

#7- After curing, the shelled waxes are put in a large autoclave in order to melt out the victory brown wax – that’s the “lost wax” part of the process. Only, the wax is not lost. It is collected, cleaned, and reused over and over, with only a small portion of it being truly “lost” in the process.

#8- The empty ceramic shells are fired, heated up to temperature, and – this is the part you’ve been waiting for – molten metal is poured into them. Our foundry poured silicon bronze, stainless steel, and aluminum.

#8- The empty ceramic shells are fired, heated up to temperature, and – this is the part you’ve been waiting for – molten metal is poured into them. Our foundry poured silicon bronze, stainless steel, and aluminum.

#9- Once the metal has cooled, the shell material must be blasted from the resulting bronze positive and the casting cut off from the bars, cups, and gates the spruer added.

#9- Once the metal has cooled, the shell material must be blasted from the resulting bronze positive and the casting cut off from the bars, cups, and gates the spruer added.

#10- All the separate pieces, if any, must be welded back together …

#11- … and then “chased” by the metal chasers. Time for the artist to pop back into the process to approve his or her “work” (to be fair, I knew numerous artists who did much if not all of their own chasing – both in wax and metal).

#12- Once the chased metal is approved by the artist, the sculpture goes to the patina department, who finish it with whatever colors and sealing it needs to begin its life as a public eyesore or private piece of art that only the artist’s parents or stoned friends will claim to understand and appreciate.

#12- Once the chased metal is approved by the artist, the sculpture goes to the patina department, who finish it with whatever colors and sealing it needs to begin its life as a public eyesore or private piece of art that only the artist’s parents or stoned friends will claim to understand and appreciate.

And that, in a nutshell, is the lost wax process.

I didn’t know any of this when I arrived, hat in hand, looking for work. I just knew that my friend worked there and, if he could be trusted, it was the kind of job you could show up half-crocked for – not that I wanted to do that, just that I appreciate working in a relaxed environment.

I was hired and thus began my career as a wax-spruing, foundry-rat.

The primary material used for both the initial wax casting and spruing was a microcrystalline, petroleum-based wax known as “Victory Brown,” so named either because of its historical use in casting armaments or because, in the fight to get the inevitable smell and stains of it out of your clothes and hair, it remained the victor.

The primary material used for both the initial wax casting and spruing was a microcrystalline, petroleum-based wax known as “Victory Brown,” so named either because of its historical use in casting armaments or because, in the fight to get the inevitable smell and stains of it out of your clothes and hair, it remained the victor.

My work station consisted of a stool at a steel wrapped counter, upon which sat a small metal rack with three soldering irons, a couple of wooden handled carving knives, an impromptu, wooden, gun-rack affair bookending a pile of foam pads, a large, wheeled “chip-box” full of foam packing peanuts, and two pots of different kinds of wax, which were kept up to temperature by resting on a shared griddle between my station and the next. Dangling down from the ceiling at every station and giving the place the air of a slaughterhouse, was a chain with a hook at its end, which I later learned were used to hang freshly sprued pieces for final clean-up and qc.

My work station consisted of a stool at a steel wrapped counter, upon which sat a small metal rack with three soldering irons, a couple of wooden handled carving knives, an impromptu, wooden, gun-rack affair bookending a pile of foam pads, a large, wheeled “chip-box” full of foam packing peanuts, and two pots of different kinds of wax, which were kept up to temperature by resting on a shared griddle between my station and the next. Dangling down from the ceiling at every station and giving the place the air of a slaughterhouse, was a chain with a hook at its end, which I later learned were used to hang freshly sprued pieces for final clean-up and qc.

With these tools, plus a large, communal vat of wax and a big, heated flattening table, we went about our day cutting up sculptured wax and affixing it with bars or “gates” of wax to cups and bars.

With these tools, plus a large, communal vat of wax and a big, heated flattening table, we went about our day cutting up sculptured wax and affixing it with bars or “gates” of wax to cups and bars.

The constant fumes and smoke generated by the liquid wax and the soldering irons created the necessity for a hardy air handling system. The strategically placed and flexible intake tubes throughout the room removed airborne particles and replaced them with a constant, ear-splitting roar. A small but notable percentage of the wax department used the hoses to their advantage, exhaling surreptitious lung fulls of marijuana smoke directly into the ever-sucking mouths of the hoses throughout the day.

The constant fumes and smoke generated by the liquid wax and the soldering irons created the necessity for a hardy air handling system. The strategically placed and flexible intake tubes throughout the room removed airborne particles and replaced them with a constant, ear-splitting roar. A small but notable percentage of the wax department used the hoses to their advantage, exhaling surreptitious lung fulls of marijuana smoke directly into the ever-sucking mouths of the hoses throughout the day.

The job was unglamorous, to say the least but featured an amazing perk (and I’m not talking about the whisking away of incidental narcotics evidence) but rather the fact that the employees were allowed to cast bronze for the cost of metal weight alone.

The job was unglamorous, to say the least but featured an amazing perk (and I’m not talking about the whisking away of incidental narcotics evidence) but rather the fact that the employees were allowed to cast bronze for the cost of metal weight alone.

You had to do yourself or trade with someone for much of the rest of the process, of course, but this meant, on a piece of metal where the professional artist was paying a couple hundred dollars, you were paying around $20. Pretty incredible.

There were limits, naturally. You couldn’t glut the process with your ashtrays and gear-shift knobs, for example, but plenty of us cast at least something, many of us regularly. Why not?

As a coworker and, later, supervisor, liked to say: “Cast as much as you can while you are here because, once you’re gone, even if you managed to cast a thousand pieces, you will regret that you didn’t cast more.” You were so right, Mike. So right it hurts.

The problem was, I had never considered myself good at art. As a matter of fact, I considered myself absolutely terrible at it. Embarrassingly so. In school, the only class I hated more than art was math and yet I spent so much of my free time making art. I just never realized it, I guess.

Anyway, I spent the first couple months or so just learning my job as a spruer, so afraid I would be terrible at it because I had never considered myself good with my hands. But I wasn’t terrible at it at all. I was good at it. Fast, clean, and capable. Sure, I was doing the kind of work you can train chimps to do – and for fewer bananas – but something inside me changed when I realized I wasn’t a complete maladroit.

Further, a lot of the sculpture that was passing by me on a daily basis simply wasn’t all that good. Some was *amazing* but the rest was either just competent or worse. Add to this the fact that the bulk of my coworkers were casting, and break-time conversations were often related to art or artistic endeavors, and what you have is an incredibly motivational environment for the creative individual, which I am.

As my job took very little brain, I was left to stew in my own, creative ideas and, soon enough, began acting on them.

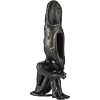

At first I just played with primitive blob figures – the sculpture equivalent of the stick figure – and told myself and others that I wanted them to appear primitive but the truth was I was too afraid and lazy to try my hand at anything too fine for fear of failure and its attendant ridicule. I’m not terribly proud of these – but I don’t hate them, either. Okay: what else you got?

Part of spruing involved packing maleable wads of wax around the gates where they connected to the piece. Warm and soft, the half-melted victory brown was a tactile pleasure to squoosh and squorsh. I pulled big, warm lumps of it to from the trough in front of the flattening table far more often than I needed to just so I could pull a Mr. Whipple on ’em. Sometimes, once I set them down, these contorted lumps would appeal to me on an aesthetic level and I would toy with them throughout the day until it was clear nothing was going to come of it – or I would take them home to work on them further.

Part of spruing involved packing maleable wads of wax around the gates where they connected to the piece. Warm and soft, the half-melted victory brown was a tactile pleasure to squoosh and squorsh. I pulled big, warm lumps of it to from the trough in front of the flattening table far more often than I needed to just so I could pull a Mr. Whipple on ’em. Sometimes, once I set them down, these contorted lumps would appeal to me on an aesthetic level and I would toy with them throughout the day until it was clear nothing was going to come of it – or I would take them home to work on them further.

Please don’t ask how I suddenly had wire loops and other small, sculpting implements at my house where, prior, none existed. All I can say is that every foundry coworker’s house I ever visited had a similar issue – a fact I noted well before finding a rag-tag set of the tools somehow migrated to my own.

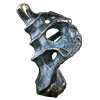

One small abstract that started out as a lump of wax became the first piece I ever had molded. “Abstrakt 1” I called it, being the creative type. I played with the contours for weeks and never really finished it to my liking but had it molded anyway. I even dreamed of casting a large version. The only one I have in metal has been further perverted by a long bath in nitric acid, which ate away a good part of the outer surface. I still have the mold, though, and found a semi-decent pour of the thing while “researching” this story.

One small abstract that started out as a lump of wax became the first piece I ever had molded. “Abstrakt 1” I called it, being the creative type. I played with the contours for weeks and never really finished it to my liking but had it molded anyway. I even dreamed of casting a large version. The only one I have in metal has been further perverted by a long bath in nitric acid, which ate away a good part of the outer surface. I still have the mold, though, and found a semi-decent pour of the thing while “researching” this story.

Other abstracts followed, using a very similar process of discovery. The similarities between “Glean” below and the wax lump image above bear this out.

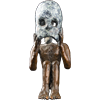

At the same time that I was squishing and squinting at wax blobs, I was also playing around with the “stalagmites” of wax that formed at our stations from the wax dripping off the hot griddles and soldering iron tips. The friend who’d gotten me the job molded a small skull decoration of mine and I built a small, fantasy scene from the two elements. My friend also made me a keychain charm from one of the skulls, which I use to this day.

At the same time that I was squishing and squinting at wax blobs, I was also playing around with the “stalagmites” of wax that formed at our stations from the wax dripping off the hot griddles and soldering iron tips. The friend who’d gotten me the job molded a small skull decoration of mine and I built a small, fantasy scene from the two elements. My friend also made me a keychain charm from one of the skulls, which I use to this day.

The foundry tended to attract and employ artistic types and most artistic types are temperamental if not just plain mental. The turnover rate and continual restructuring, as people moved from department to department, was bewildering. One month a coworker was a spruer, then a welder, then a patineur, then a salesman – then fired.

There was lots of disgruntlement as just-above minimum-wage employees helped sculpt art that was sold for thousands. It didn’t help that the job cards, which followed the pieces throughout the process at the foundry, detailed what the client was paying for each step. The disparity between the price paid versus the pay received was a bit startling but, of course, the employee never considers the cost of materials, insurance, maintenance, etc that goes into keeping them employed and the foundry running – they just want to know why the client is paying $75/hr for a job they’re getting $9/hr for.

The friend who’d gotten me the job decided that he simply wasn’t being paid enough for his efforts so, every day, a half hour before quitting time, he’d cross his arms and just sit there, doing nothing. When I asked him what he was doing he told me he was giving himself a raise. I told him he was giving himself a one way ticket to the unemployment line. He didn’t care. It didn’t matter to him that he’d *agreed* to work at such a wage, he felt he deserved more – and so they busted him down to wax pour. Eventually, he became so miserable that he left the foundry altogether and began work at another, where he was again, eventually busted down to wax pour.

To be fair, management was no picnic. The head of the operation, somebody’s rich son, as the story went, was loathed and ridiculed by virtually all the employees. When he’d finally had enough, he brought in a surrogate. We were all pretty hopeful at first. The new guy called in the heads of all the departments for private talks to hear their ideas. Then he threw a big, after work party with pizza, beer, and a pep-talk of monumental proportions. I was given a cash award for pressing forward on a long-since departed coworkers’s idea on how to replace and improve the wooden “gun-racks” we used for spruing the large and fragile monument panels. I was also made head of monument sprue; a team created on the spur of the moment for all the monuments we were lined up to cast.

To be fair, management was no picnic. The head of the operation, somebody’s rich son, as the story went, was loathed and ridiculed by virtually all the employees. When he’d finally had enough, he brought in a surrogate. We were all pretty hopeful at first. The new guy called in the heads of all the departments for private talks to hear their ideas. Then he threw a big, after work party with pizza, beer, and a pep-talk of monumental proportions. I was given a cash award for pressing forward on a long-since departed coworkers’s idea on how to replace and improve the wooden “gun-racks” we used for spruing the large and fragile monument panels. I was also made head of monument sprue; a team created on the spur of the moment for all the monuments we were lined up to cast.

My very first job in this position had me overseeing the spruing of a massive monument, panel after panel of which I allowed to pass through the process *unmarked* to fit the scheme map that came with it, meaning the welders had to do their best to puzzle it out on the metal floor. Boy was I popular. I never made that mistake again, I can assure you.

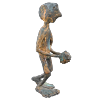

Watching a show on traditional, African art one evening, I had the idea of a figure with a big, flat, nearly two-dimensional face atop a more normally rounded body. I set to work on it and had my finished product pretty quickly. It still had the primitive aesthetic I had claimed I wanted before but now I actually *did* like it. I was especially happy with the laced fingers.

I stuck a medium-sized sprue to its back and ran a couple of spaghetti gates to its extremities. My supervisor, took one look and laughed. “That’ll never pour, man,” he clucked. “All those little, thin parts? All the detail? No matter how you gate it, it’s going to pour short. That needs to be vacuum cast if you want it to have a chance of surviving.”

Vacuum casting? I’d heard of it before and knew we were one of the few big foundries in town to employ the process, more typically used in the jewelry trade because of its ability to get around the bubbles and short pours associated with smaller, thinner parts and detail.

Vacuum casting uses a special, finer shell material or “investment” than the larger pieces and all the items cast in this way have to fit within the circumference of a “flask:” tall, metal tubes that are placed over the vertical sprue tree and filled with the investment. While this investment is still wet, the cans are placed in a vacuum chamber which pulls all the air out of the investment, forcing it to fully collapse around the delicate forms within, producing a much finer mold. Further, the main gate of the sprue tree is far greater in mass in relation to the pieces which are attached to it than is so of the more traditionally cast pieces. This extra room in the gate assures greater fluid pressure on the hollows in the mold after the wax has been melted out and the molten metal is poured in.

I was excited by this alternative process and thereafter assisted my supervisor whenever we did it. Because we didn’t always have pieces requiring such special care, vacuum casting flasks were rarely part of a pour but, when they were I always tried to have a piece for the tree.

That first time out, I cast not just the aforementioned little fellow with the flat head but a piece I like even better – “Galumph” – a crude Seussian elephant in miniature.

I also decided to cast The Padisha Emperor Buddha – a collaborative piece that I and a short-term station-mate fashioned in a couple of weeks between swipes at sprue gates. I’d hoped the thing would grow and change and become more elaborate as we worked on it (it started out as a simple pinch of victory brown) but my partner in this particular crime only lasted about a month at the job and, truth be told, was never as taken with the idea as I was. Still, being a devotee of frequent acid trips and the musical stylings of Dr. Octagon, his additions are what gave the resulting blob of stupidity the little, surreal charm it does have.

I also decided to cast The Padisha Emperor Buddha – a collaborative piece that I and a short-term station-mate fashioned in a couple of weeks between swipes at sprue gates. I’d hoped the thing would grow and change and become more elaborate as we worked on it (it started out as a simple pinch of victory brown) but my partner in this particular crime only lasted about a month at the job and, truth be told, was never as taken with the idea as I was. Still, being a devotee of frequent acid trips and the musical stylings of Dr. Octagon, his additions are what gave the resulting blob of stupidity the little, surreal charm it does have.

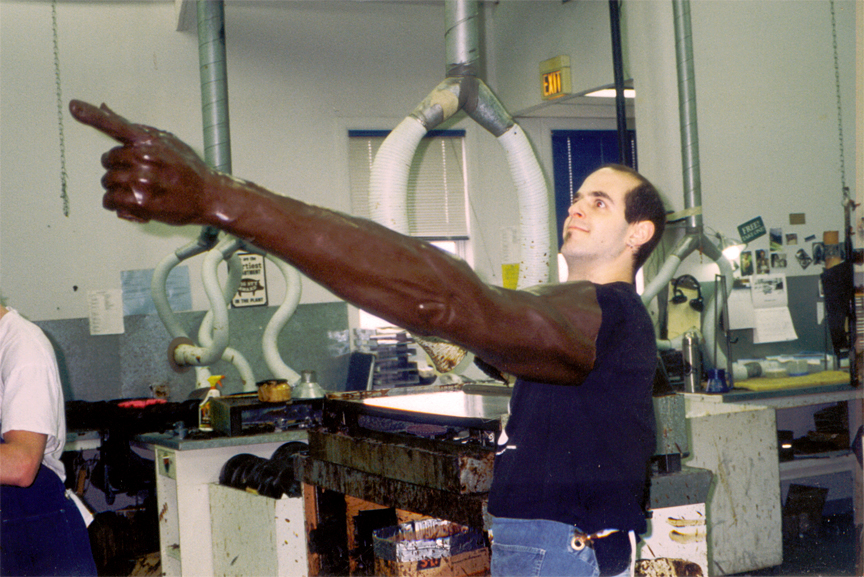

Ever fascinated with the concept of life casting, I made a large number of decent, single-finger castings by coating a digit with wax, chilling it, spraying the resulting negative with a mold-release serendipitously named “Stoner,” then filling it with wax. I discovered that spraying in too much Stoner would produce a bubbly positive, which somteimes looked pretty cool. So cool, in fact, that I cast one.

Ever fascinated with the concept of life casting, I made a large number of decent, single-finger castings by coating a digit with wax, chilling it, spraying the resulting negative with a mold-release serendipitously named “Stoner,” then filling it with wax. I discovered that spraying in too much Stoner would produce a bubbly positive, which somteimes looked pretty cool. So cool, in fact, that I cast one.

I became so adept at this simple process that I decided to go one step further and cast my entire hand (in double-joint display position, natch) by dipping it into the big wax vat one painful layer at a time over lunch. Victory Brown melts at 175º F! Damned stupid but I was surprised at just how good it came out.

I became so adept at this simple process that I decided to go one step further and cast my entire hand (in double-joint display position, natch) by dipping it into the big wax vat one painful layer at a time over lunch. Victory Brown melts at 175º F! Damned stupid but I was surprised at just how good it came out.

Back on the vacuum casting front, I decided to create something creepy for myself: a corpse in a coffin. I worked long and hard on the piece, playing with it until the details were just to my liking. Best of all was the coffin, which I fashioned from thin, sheet wax, dipped into victory brown, and then carved to look like wood grain. At the last instant my older brother, who now worked alongside me in the sprue department, convinced me to put a crack in the coffin lid. I couldn’t see what he was thinking at all but, dutiful little brother that I am, I hacked that stupid looking y in it with a soldering iron and sprued it up after screwing it up. I don’t know what the hell I was thinking. So stupid – go sculpt your own damn coffin and leave this idiotic sycophant alone, wouldja?

Still, the piece came out great and, when a contractor disparaged its dimensions and execution with unnecessary cruelty one afternoon, I realized a couple of things. First, I understood almost immediately that the guy only wanted to knock it down a peg because, despite the dumb crack and his complaint that the figure’s feet were too big, it was obvious he thought it was cool as hell and was jealous. Second, I knew that it wasn’t perfect and even took the time to show him that the feet were big so that the figure could stand, ala Karloff’s Mummy, but I liked it a lot and his comments didn’t phase me for a second. Even if they hadn’t been said out of jealousy but honest criticism it wouldn’t have mattered because the piece succeeded for its target audience: me.

Still, the piece came out great and, when a contractor disparaged its dimensions and execution with unnecessary cruelty one afternoon, I realized a couple of things. First, I understood almost immediately that the guy only wanted to knock it down a peg because, despite the dumb crack and his complaint that the figure’s feet were too big, it was obvious he thought it was cool as hell and was jealous. Second, I knew that it wasn’t perfect and even took the time to show him that the feet were big so that the figure could stand, ala Karloff’s Mummy, but I liked it a lot and his comments didn’t phase me for a second. Even if they hadn’t been said out of jealousy but honest criticism it wouldn’t have mattered because the piece succeeded for its target audience: me.

It was on that day that I came to fully realize that one must do art for one’s self, first or never realize contentment. Certainly you may end up being the only one who likes the work but – hey: *you* like it, so screw ‘em! Also, put your ego down, bub. You’re not as unique as you’d like to think. If you like it, sure as heck someone else will, too, so quit worrying about other people and just go for it!

I have since been offered *hundreds* for this piece and others but I couldn’t let them go because they mean so much more to me. Take that, naysayers.

With this new sense of artistic self, I began a trio of figures based on an initial bit of fooling around I did at a coworker’s sculpting party. The coworker, a multi-talented welder named Jeff, was a serious artist, albeit a young and struggling one. Gregarious and dedicated, he’d set up a garage on his rented property as a full studio and, when he had sculpting parties there, it was expected that you’d come in, grab a beer or a toke and a wad of wax and work on something – anything! – throughout the evening, then leave it in his studio when you were done.

I was done within minutes of arriving, and I don’t mean with my impromptu sculpture. Stumbling over to the pan of wax lumps floating in hot water, I selected one for my own and immediately shoved my thumb deep within its core. It felt good in there, all tight and warm and wet. Almost like a … I looked down and there was a misshapen, brown lump on my thumb. I didn’t know what the hell it was. Others were walking around with little abstracts or faces or whatever and here I was, looking like Little Jack Horner after a visit to the loo.

I quickly smoothed out the lump, elongating it and shaping it into, uh. I still had no idea but then it began to look like a mouth and the queerest idea hit me. An idea of a figure with wide, empty eyes and a mouth that spiraled away to nothing.

Instead of leaving the piece on the shelf as I was supposed to, I snuck it out to my car and took it home, adding a body of similar, primitive detail as the one on “Clasp.” I carved symbols into the back of the creature’s head, and wrapped the thing’s nightmare mouth around its butt like a tail. I called it “Theos” and imagined the others, each one an aspect of man’s way of dealing with the nature of being.

“Theos” represents those who believe in mysticism and divinity: huge, sightless eyes; a reliance of ancient and incomprehensible symbols for power and faith; a mouth that spirals ever on to nothing in an attempt to explain what would not need explaining were it true.

“Theos” represents those who believe in mysticism and divinity: huge, sightless eyes; a reliance of ancient and incomprehensible symbols for power and faith; a mouth that spirals ever on to nothing in an attempt to explain what would not need explaining were it true.

“Agnos” represents those who refuse to believe or disbelieve in divinity: holding up a stark white partial and broken actor’s mask in a failed attempt to conceal the lack of any head at all. The mask on this one was another lump of wax shoved over my thumb and then sculpted to appear both face like and broken.

“Agnos” represents those who refuse to believe or disbelieve in divinity: holding up a stark white partial and broken actor’s mask in a failed attempt to conceal the lack of any head at all. The mask on this one was another lump of wax shoved over my thumb and then sculpted to appear both face like and broken.

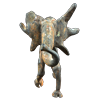

“Athos” represents those who refuse all notions of spirituality or the divine: also lacking a head, three sets of arms branch out from the shoulders and bring the hands together to mimic the shapes of eyes, a nose and a mouth, indicating that Athos creates his own reality from only that which he can touch to ascertain is real.

“Athos” represents those who refuse all notions of spirituality or the divine: also lacking a head, three sets of arms branch out from the shoulders and bring the hands together to mimic the shapes of eyes, a nose and a mouth, indicating that Athos creates his own reality from only that which he can touch to ascertain is real.

“Theos” and “Agnos” were cast in the same session but “Athos,” as you can probably tell from the description, was a bit more daunting. I got the idea for his face from the Jim Henson movie “Labyrinth” (natch) and actually managed to do a rough sculpt of all the parts for the piece but I never managed an actual assembly or cast. Surprisingly, a few of the pieces have survived the intervening years and, if I ever have the opportunity to vacuum cast bronze again, “Athos” will be job #1.

[…] (Part 1 of “Lost and Foundry” can be found here) […]

[…] a recent post, I mentioned having worked at a bronze foundry close to 20 years ago (“Lost and Foundry”) and the sense of family that the place left me with, despite all the time and distance that has […]