(Part 1 of “Lost and Foundry” can be found here)

The longer I worked at the foundry, the farther I rose up in ranks – whether I wanted to or not – and it wasn’t just because of my abilities.

First there was the appointment to head of Monument Sprue, a change that mainly involved me going to lots of pointless meetings and wandering around the foundry with a clipboard, talking to friends – not because it was part of the job but because the position and clipboard gave me the excuse and camouflage to do so. Then they allowed me to move to patina and, in short order, made me head of that department.

But wait – I’m getting ahead of myself (foreshadowing pun intended):

The biggest piece I ever attempted began as just another cheap way of molding things. I don’t recall if we had aluminum foil on hand in the sprue department or if I brought it from home but I conceived of an idea using it as a mold material; a mold material for my own head.

Rather than do it all in one go, which wouldn’t work, I decided to mold small portions of my noggin and then stitch the pieces together, once they were in wax. My friend, who’d gotten me the job, was now working in wax pour. He happily obliged my strange idea, pouring layers of wax onto my little, foil panels, in between his legitimate work. Before long, they were all done and it was time to construct the head.

I worked on it at home, nights and, as it came together, I could see how eerie it would be, wrinkly and disproportionate, almost like a hydrocephalic bog-mummy. I loved it and conceived of molding further parts of my body: one leg and six variations of my arms to be assembled in a repulsive, horizontal creature reminiscent of something out of John Carpenter’s “The Thing.” That’s when I came up with the title: “Narcissus Gone Awry.” I knew it should be “Narcissism,” not “Narcissus,” but preferred the sound of the latter.

I worked on it at home, nights and, as it came together, I could see how eerie it would be, wrinkly and disproportionate, almost like a hydrocephalic bog-mummy. I loved it and conceived of molding further parts of my body: one leg and six variations of my arms to be assembled in a repulsive, horizontal creature reminiscent of something out of John Carpenter’s “The Thing.” That’s when I came up with the title: “Narcissus Gone Awry.” I knew it should be “Narcissism,” not “Narcissus,” but preferred the sound of the latter.

Once I got it tacked together and chased to my liking, I brought the finished piece into work and rested it in my chip box. People either found it creepy (one joker suggested I was building it as a workaround for achieving auto-fellatio – cute, Ray. Very cute.) or liked it quite a bit – maybe even as much as I did.

I paid to have the head molded and a number of them poured.

Once I got it tacked together and chased to my liking, I brought the finished piece into work and rested it in my chip box. People either found it creepy (one joker suggested I was building it as a workaround for achieving auto-fellatio – cute, Ray. Very cute.) or liked it quite a bit – maybe even as much as I did.

I paid to have the head molded and a number of them poured.

I ended up giving three of them away. One was never poured. Another – the one I cast, chased in metal and finished – went to an anarchist friend and fellow foundry-rat, who probably lost it in an unpaid storage unit after he expatriated to Costa Rica in response to George W. Bush gaining the presidency. The third went to my friend who helped me get the job and also poured much of the initial, foil panels. I was surprised to learn, some decades later, that he was toting a picture of it around in his portfolio and claiming partial credit for the idea. This is the same guy who, back in our foundry days, listened to my idea for a piece, then proceeded to create it, responding when I confronted him with: “you were never going to do it, anyway, dude.” Despite these things, I’m still friends with the guy. What can I say? He’s like a brother and, besides, he taught me a valuable lesson: Keep your ideas to yourselves, folks.

I took a wax of the head home and began working on the leg, attaching the two pieces together when the latter was completed. It looked great – half the piece was done! – but then I ran into a roadblock: Mr. Independent was going to need assistance molding his arms and hands in aluminum foil. It was also clear that an armature of some sort would be required to hold the bloody thing aloft for assembly. The project was blossoming into something far more serious than I had initially conceptualized. It was daunting. I discussed ideas for approach with friends and fellow artists but never actually asked for any help and the project lingered when, as I said before, I was moved to patina and, shortly thereafter, made head of the department.

I took a wax of the head home and began working on the leg, attaching the two pieces together when the latter was completed. It looked great – half the piece was done! – but then I ran into a roadblock: Mr. Independent was going to need assistance molding his arms and hands in aluminum foil. It was also clear that an armature of some sort would be required to hold the bloody thing aloft for assembly. The project was blossoming into something far more serious than I had initially conceptualized. It was daunting. I discussed ideas for approach with friends and fellow artists but never actually asked for any help and the project lingered when, as I said before, I was moved to patina and, shortly thereafter, made head of the department.

And how did I end up as head of patina, you ask?

Well, management under the new guy got worse than it had been before. He alienated virtually everyone. Customers and employees fled – so many, in fact, that my long-time dream of working in the patina department was realized not because I displayed the requisite skill but because we were in desperate need of warm bodies back there! Three months in, I was made head of the department because … everyone above me left.

Well, management under the new guy got worse than it had been before. He alienated virtually everyone. Customers and employees fled – so many, in fact, that my long-time dream of working in the patina department was realized not because I displayed the requisite skill but because we were in desperate need of warm bodies back there! Three months in, I was made head of the department because … everyone above me left.

Now, patina is not one of those jobs you can just pick up in a few weeks or months. It is a skill. An art that takes time, dedication, finesse, and an eye that one only masters after a long and disciplined apprenticeship – and here I was running the department? Luckily, I had help from all corners, including the ever gracious and amazing, master of all things patina, Patrick V. Kipper.

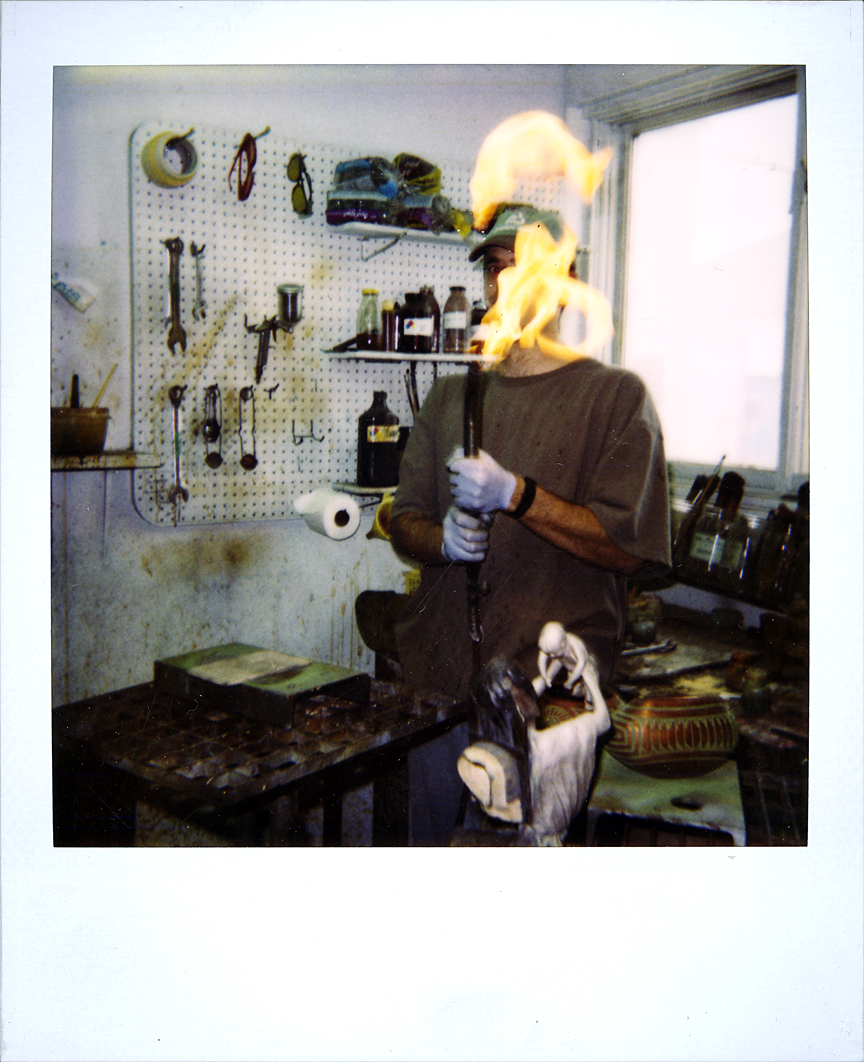

Patina was initially used to mimic age on a piece, then evolved from there. Though there are almost as many ways to create a patina as there are finishes to apply, we primarily used hot application, which consists of heating the metal with an oven or propane torch, then applying a chemical mixture, such as ferric nitrate – essentially rust and acid – to the heated surface with a natural fiber or air brush.

Patina was initially used to mimic age on a piece, then evolved from there. Though there are almost as many ways to create a patina as there are finishes to apply, we primarily used hot application, which consists of heating the metal with an oven or propane torch, then applying a chemical mixture, such as ferric nitrate – essentially rust and acid – to the heated surface with a natural fiber or air brush.

The single most common patina, when I was involved in finishing bronzes, was french brown and it fits the above profile like a pale, sweaty hand in a snug, rubber glove.

#1- Put on your blue, nitril gloves to keep your filthy, staining body oils off the piece. Set the piece inside the hood of the sandblaster and blast the finished metal clean of any oils and uneven finishes left over from the welding and chasing process. The surface will now have a uniform, fine toothing for the proposed patina to bite upon.

#1- Put on your blue, nitril gloves to keep your filthy, staining body oils off the piece. Set the piece inside the hood of the sandblaster and blast the finished metal clean of any oils and uneven finishes left over from the welding and chasing process. The surface will now have a uniform, fine toothing for the proposed patina to bite upon.

#2- Place your freshly blasted piece on a grate over the sink, get it nice and wet, and start squirting it with a liver of sulfur mixture. This is a pale yellow to orange chunky chemical, also known as sulfurated potash, that dissolves in water. With the right ratio of liver to water, the solution will stain the raw bronze a dark bluish gray and fill the air with the heavenly scent of rotting eggs.

#3- Once the piece is a fairly even gray color, get out your red, scotch-brite pad and start scrubbing the liver of sulfur back *off* the piece until only the recesses retain its hue, giving the piece a richer sense of contrast. This is best done with plenty of water. Oops: tore a glove. Better get another. Hard to put on over wet hands, aren’t they? Oh, you wore that pad out, better get another one. Now your other glove’s torn and you’ve stubbed your thumb – bet you didn’t know you could do that. Now it’s time to get the steel wool and buff out those scotch-brite scratches. Whoops-a-daisy: tore another glove and you can’t feel your hands anymore. Are your arms are shaking? Isn’t patina FUN?!?

#4- Once you have knocked back the liver of sulfur to your liking, haul the dripping, stinky bronze over to your patina stand, grab your propane torch, pop it alight, and begin heating the piece. This will chase the remaining moisture out of it and bring it up to heat. Rotate the piece on your stand as you go, concentrating on the thicker bits and avoiding overheating the thinner ones; you can’t rush this.

#4- Once you have knocked back the liver of sulfur to your liking, haul the dripping, stinky bronze over to your patina stand, grab your propane torch, pop it alight, and begin heating the piece. This will chase the remaining moisture out of it and bring it up to heat. Rotate the piece on your stand as you go, concentrating on the thicker bits and avoiding overheating the thinner ones; you can’t rush this.

#5- Okay, the metal is a nice honey yellow, indicating you’re in the right temperature neighborhood. Slip on your respirator, pop on the overhead hood to suck any excess chemical fumes away, and grab your airbrush, pre-loaded with ferric nitrate. Give the piece a test spray to see if it’s really up to temp. Did the ferric just seem to vanish into the surface? Good. If it’s visible and bubbling, you’re too cold. Making an obvious stain? You’re too hot. Keep spraying in a steady, circular motion until you see the color start to come up. Don’t stay in one spot but rotate the piece. There you go – not too much now. Not too fast and not too slow.

#6- When you have the surface up to a nice even coat of the color you want – a rich, deep red on the highlights is good – put down your airbrush, kill your torch, and whip out a can of Johnson’s Paste wax. Using a natural-fiber brush, start dabbing the paste wax on the hot metal until the entire surface has a good coat. Alternately, you can allow the piece to cool, then spray it with specially formulated lacquer but be sure to wear your respirator or, well, you’ll start to enjoy your job a little *too* much.

#7- Once the piece has cooled and the wax has dulled, get in there with a soft cloth and buff it out – oop! Stubbed your pinky this time! Smarts, don’t it? Hey, that’s okay – you’re finished, and just in time for the artist who … aw, heck – they meant a *French* brown, not what you have here. This just won’t do – no, no, no. Back to the sandblaster.

#7- Once the piece has cooled and the wax has dulled, get in there with a soft cloth and buff it out – oop! Stubbed your pinky this time! Smarts, don’t it? Hey, that’s okay – you’re finished, and just in time for the artist who … aw, heck – they meant a *French* brown, not what you have here. This just won’t do – no, no, no. Back to the sandblaster.

And that, in a nutshell, is a hot patina.

I had some great, patient teachers and proved myself a fast learner. Soon I was doing passable versions of most basic patinas and even a few of the intermediate ones. I was good with an airbrush but came to love doing patinas with a big, round, camel hair brush. You can really feel when the surface is ready for the chemical with a brush, the sensation of it biting into the metal somehow transmitting up through the bristles and wooden handle to your hand.

At one end of the room, where I had my station, there was a metal, fire cabinet chock full of different chemical compounds for use in patina: silver nitrate, titanium oxide, potassium permanganate, cupric nitrate, zinc sulfate, stannic oxide, sodium thiosulfate, chromium oxide, bismuth nitrate, and more. Then there were the paints, the sealers, the recipes for hot patinas, cold patinas, buried patinas, vapor patinas, splatter patinas, acrylic patinas, metal dyes – it was endless. Suddenly, all of the pieces I had waiting in bronze for a friendly, eager patineur just dying to experiment with finishes on them had one: me!

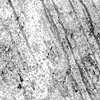

One wall of our patina room held bronze, sample tiles for customers to choose finishes from and as a reference for those of us performing the jobs. I would practice patinas on sandblasted versions of these tiles in between the real jobs. One finish, Moroccan Blue – a combination of cupric nitrate and titanium oxide, applied in rings over a surface of M20 (gun blue) –

One wall of our patina room held bronze, sample tiles for customers to choose finishes from and as a reference for those of us performing the jobs. I would practice patinas on sandblasted versions of these tiles in between the real jobs. One finish, Moroccan Blue – a combination of cupric nitrate and titanium oxide, applied in rings over a surface of M20 (gun blue) –  caught my eye and, after getting it down, I put it on my piece “Glean.” The patina has darkened some over the years but it still looks pretty good to my eye, especially considering I’d been in patina but a few weeks at the time.

caught my eye and, after getting it down, I put it on my piece “Glean.” The patina has darkened some over the years but it still looks pretty good to my eye, especially considering I’d been in patina but a few weeks at the time.

I applied Gold Flash – ferric nitrate rings over a surface of silver nitrate – to “Abstrakt2” but the piece (and my experience in applying it) was too small for the full effect of the patina to work as intended. Instead of light gold veins on a dark background, the entire piece is a mottled golden amber – oh, well, it still looks good.

I applied Gold Flash – ferric nitrate rings over a surface of silver nitrate – to “Abstrakt2” but the piece (and my experience in applying it) was too small for the full effect of the patina to work as intended. Instead of light gold veins on a dark background, the entire piece is a mottled golden amber – oh, well, it still looks good.

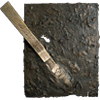

Now my free thoughts turned from sculpting (modeling, really) in wax to finishing in patina. It was around this time that I got the idea for “bronze painting.” I took a piece of watercolor paper and dipped it in the big wax vat up in sprue in order to thicken it, then, using a paintbrush, dabbed at my “canvas” with slightly cooler wax, building up layers and textures as I went, like one might with oil color.

The idea was to create a “painting” using wax, then cast the thing and patina on the colors. Pretty cool idea, eh? I still haven’t seen anyone do it – and now I’ve given the idea away as I claim to have learned not to. Hah!

Anyway, the only real problem with the idea was I’d never painted with oil before and was only familiar with the rudiments of working in watercolors or acrylics. Consequently, instead of a monochrome painting in wax, what I had were a bunch of chunky blobs on a relief panel.

Still, I felt the effect looked cool – different – so I tacked on some other bits and sent them through. “Spar” was finished by a friend while the patina on “Good Morning” was applied by yours truly.

Still, I felt the effect looked cool – different – so I tacked on some other bits and sent them through. “Spar” was finished by a friend while the patina on “Good Morning” was applied by yours truly.

Another relief panel I tried to get through the process was based off two castings of my teeth, made by my orthodontist while I was but a teen: one before braces and one after. I had them molded and poured a number of them for the proposed relief panel. Its working title was “Pretty Ugly,” a play on the alternating design. I forgot all about it until digging through my remaining waxes for this post revealed a bag of grins and, with it, the echoes of a voice saying “you will regret having not cast more.”

Another relief panel I tried to get through the process was based off two castings of my teeth, made by my orthodontist while I was but a teen: one before braces and one after. I had them molded and poured a number of them for the proposed relief panel. Its working title was “Pretty Ugly,” a play on the alternating design. I forgot all about it until digging through my remaining waxes for this post revealed a bag of grins and, with it, the echoes of a voice saying “you will regret having not cast more.”

Patina could be great and patina could be really horrible. A lung full of leftover cupric nitrate vapor would leave you feeling on the verge of the flu for hours. Watching colors bloom at the end of your brush bristles and rich, engrossing depth suddenly appear with the application of lacquer or wax never got dull. It felt like magic. I loved doing faux, organic finishes on small, abstract pieces and hated monuments or any life-sized piece, really. They were just tedious and horrible, especially that initial coat of liver. A coworker once compared the job of patina to that of an overrated dishwasher. Apt but I preferred that concept to what it turned into with the larger pieces – an overrated car-washer. Cars with rough, uneven surfaces. I always felt like I was polishing some idiot’s ego.

Patina could be great and patina could be really horrible. A lung full of leftover cupric nitrate vapor would leave you feeling on the verge of the flu for hours. Watching colors bloom at the end of your brush bristles and rich, engrossing depth suddenly appear with the application of lacquer or wax never got dull. It felt like magic. I loved doing faux, organic finishes on small, abstract pieces and hated monuments or any life-sized piece, really. They were just tedious and horrible, especially that initial coat of liver. A coworker once compared the job of patina to that of an overrated dishwasher. Apt but I preferred that concept to what it turned into with the larger pieces – an overrated car-washer. Cars with rough, uneven surfaces. I always felt like I was polishing some idiot’s ego.

The heat in the room on hot summer days, what with all the torches blazing away, could be insane. Some sadistic bastard had hung a thermometer up on the wall in there and one time it topped out at 126°F! This ever-present heat, combined with the back-splash and constant vaporous cloud of patina chemicals and sealers meant that you’d be sweating when applying the patina and then soaking up the chemicals with your skin as you cooled off in between jobs. I would always shower the minute I got home, at the very least to get rid of the liver smell but, well into the position, my wife complained I was retaining more than I realized, more than soap could wash off. Being a typical, younger man with illusions of immortality, I pooh-poohed her concerns until she showed me the mattress pad which, on my side, was stained a deep ferric red.

Further, as mentioned above, sometimes the tasks at hand were outside my skill level. Finishing a multi-thousand dollar piece of installation bronze with the artist sitting right there, watching you while you’re all too aware that you have NO IDEA WHAT YOU ARE DOING, can be a little bit stressful, could cause you to be a mite tense.  I once beat a dual-cassette, stereo boombox to itty-bitty, little pieces with a tank wrench and a throat-raking bellow while my coworkers looked on. “Nice scream of inarticulate rage, man,” one commented as I swept up the bits. Business as usual in the patina department. We definitely should’ve worn our respirators a bit more regularly.

I once beat a dual-cassette, stereo boombox to itty-bitty, little pieces with a tank wrench and a throat-raking bellow while my coworkers looked on. “Nice scream of inarticulate rage, man,” one commented as I swept up the bits. Business as usual in the patina department. We definitely should’ve worn our respirators a bit more regularly.

It was a mixed blessing, having the opportunity to work directly with the artists. Some of these folks are just fabulous – immensely talented, down-to-earth individuals that respectfully leave you to your work or engage you in friendly conversation. Others are egotistical, aloof, demanding, or unhelpfully intrusive.

I had one artist who drove me – and many others – bonkers for weeks, insisting that, of all things, I didn’t know how to do a proper french brown. Admittedly, the first one rejected *was* wrong but, thereafter, no version of the classic, simple patina I executed would satisfy her.

I had one artist who drove me – and many others – bonkers for weeks, insisting that, of all things, I didn’t know how to do a proper french brown. Admittedly, the first one rejected *was* wrong but, thereafter, no version of the classic, simple patina I executed would satisfy her.

The first piece was sent back because the tone was too light. Receiving it, we had to agree: our mistake. So, I redid it and, at the metal-floor manager’s suggestion, sent her a picture of the finished piece for approval prior to shipping, which we received. Okay – off it goes.

Upon receipt we hear that, no, it’s still wrong. Back it comes – all on our dime, of course.

Meanwhile, numerous iterations of it are backing up on the shelf, along with many other artist’s pieces. We repeat this game two more times and finally management steps in – this is abuse of the system. Everyone knows the patina I’m achieving is fine but the artist insists it is not. Even legendary patineur, Pat Kipper, helps via phone. Gracious man that he is, and having done many patinas for said artist, he offers some suggestions, which I try. Again, the results are accepted photographically only to be rejected upon receipt.

On the phone with me, the artist is calm but condescending in the extreme, treating me like some mentally challenged child – and not just me but the metal-floor manager and the production manager, as well. Finally, she sends up her own, pet patineur who “teaches” me how to do a french brown. Gee, this recipe and process seems awfully familiar …

We perform the finish on a face from one of her other pieces, poured for just this purpose, which is taken back for her approval. Lo and behold, it is accepted. The metal face is then sent back to us to be used not only as a guide but also to be photographed next to every piece of hers involving said patina for her remote approval. We hang this face on the wall like some horrible, reverse trophy and it leers down at me, daily. As soon as the run of pieces is completed the artist quits casting with our foundry.

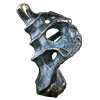

The upside to all of this is that I got to keep the sample face. The metal-floor manager wanted to beat it with a hammer or take a plasma-torch to it but I, being the person who suffered the most indignity throughout the process, was allowed to decide its fate. I took it down from the wall and poured a big splorp of tool dip onto it.

The upside to all of this is that I got to keep the sample face. The metal-floor manager wanted to beat it with a hammer or take a plasma-torch to it but I, being the person who suffered the most indignity throughout the process, was allowed to decide its fate. I took it down from the wall and poured a big splorp of tool dip onto it.

Tool dip is a rubbery liquid sold to dip the handles of your tools into. You dunk them in and allow the glop to set up, providing a comfortable, protective sheath on the handle, the likes of which you have undoubtedly seen on numerous tools throughout your life. In patina, we used it on rare occasions as a masking tool. Most of the time, you didn’t need a mask as precise as the kind tool dip could provide but, every once in a while it would come in handy.

Anyway, I allowed the tool dip splop to cure, then hauled the face over to the sandblaster and blew all the unprotected finish off the thing. Then I chucked it onto the sink grate, livered the crap out of it, plopped it onto my patina stand, and browned up the liver on the face with a hearty spray of ferric. I gave the otherwise black hair a white wash of titanium oxide. Peeling off the tool dip, I pencil ground the eyes and added silver nitrate to the irises. Once cool, I sealed it with lacquer: voila. It hangs on the wall of my house to this day. Finally, one of those sculptures is interesting.

Anyway, I allowed the tool dip splop to cure, then hauled the face over to the sandblaster and blew all the unprotected finish off the thing. Then I chucked it onto the sink grate, livered the crap out of it, plopped it onto my patina stand, and browned up the liver on the face with a hearty spray of ferric. I gave the otherwise black hair a white wash of titanium oxide. Peeling off the tool dip, I pencil ground the eyes and added silver nitrate to the irises. Once cool, I sealed it with lacquer: voila. It hangs on the wall of my house to this day. Finally, one of those sculptures is interesting.

Speaking of pencil grinders, I learned a very important, personal-safety lesson through one of them while working in patina.

A pencil grinder is a thin, hand-held air tool, not unlike a Dremel but much thinner, thus the name. Our metal chasers used them all the time for both grinding and polishing. In patina, we used them on to do fine polishing in tight places. Instead of a metal burr, there were these little, abrasive, rubber bullets from Cratex. Shaped not unlike long pencil erasers, they are riddled throughout with metal fibers and tapered at the end. They’re designed to fit over the grinder’s bit and do a wonderful, fast job of bringing up polish. They break pretty easily until they wear down some, though and, when they do, fly off the high-rpm bit … like a bullet. I used them here and there but, for some reason, always eschewed eyewear while doing so. My reasoning was, if I pointed the grinder directly away from myself when grinding, the potential missile would shoot out following the circle of rotation: to the side, ceiling, or floor – not straight ahead or back at me. I mean, when you’re flung off a merry-go-round, you don’t go shooting straight up into the air, do you? Seems like sound reasoning, right? Boy, was I wrong.

A pencil grinder is a thin, hand-held air tool, not unlike a Dremel but much thinner, thus the name. Our metal chasers used them all the time for both grinding and polishing. In patina, we used them on to do fine polishing in tight places. Instead of a metal burr, there were these little, abrasive, rubber bullets from Cratex. Shaped not unlike long pencil erasers, they are riddled throughout with metal fibers and tapered at the end. They’re designed to fit over the grinder’s bit and do a wonderful, fast job of bringing up polish. They break pretty easily until they wear down some, though and, when they do, fly off the high-rpm bit … like a bullet. I used them here and there but, for some reason, always eschewed eyewear while doing so. My reasoning was, if I pointed the grinder directly away from myself when grinding, the potential missile would shoot out following the circle of rotation: to the side, ceiling, or floor – not straight ahead or back at me. I mean, when you’re flung off a merry-go-round, you don’t go shooting straight up into the air, do you? Seems like sound reasoning, right? Boy, was I wrong.

One morning, I’m polishing a small ridge on a piece when the fresh bullet I am using develops a wobble and breaks, shooting non-intuitively right back into my face at full velocity. Right into my left eye, to be exact. It’s like being slapped but on the eyeball and I immediately know something is wrong: it’s hard to blink. I can see out of the eye but the vision is blurry, the eye stings, buzzes, and keeps tearing up. It feels like something is sticking out of it; a lump or a flap – I hope to hell not some chunk of the damned Cratex bullet.

One morning, I’m polishing a small ridge on a piece when the fresh bullet I am using develops a wobble and breaks, shooting non-intuitively right back into my face at full velocity. Right into my left eye, to be exact. It’s like being slapped but on the eyeball and I immediately know something is wrong: it’s hard to blink. I can see out of the eye but the vision is blurry, the eye stings, buzzes, and keeps tearing up. It feels like something is sticking out of it; a lump or a flap – I hope to hell not some chunk of the damned Cratex bullet.

A passing coworker, previously an EMT, as luck would have it, sees me holding my face and comes over. “Oh, yeah: your cornea’s all jacked up, dude. You need to go to a doctor, stat.” Great.

I punch out and drive myself to one of those first care places, tears of physical irritation running down my cheeks as I navigate the roadway. It feels like there’s a pea under my left eyelid and the discomfort is becoming greater. It’s hard to concentrate, to keep from shaking my head like a drunken bear, but somehow I make it to the doctor’s office without crashing into something. The attending physician has me lie down in a dark room and puts some kind of glowing dye into my eye. The darkness and solution soothe my discomfort some and I note a green glow coming from my eye injured eye socket. What the hell did she put in there? The doctor peers down at me and pronounces my injury the worst corneal tear she’s ever seen. I feel a mixture of dread and pride. She verifies that the wound is clean, puts in some kind of medicine, and tapes a pad over my eye.

“Take it easy and you should be back to near-normal by tomorrow morning.”

What? Really?

Really.

I awake the next day with little to no physical awareness that I’ve had any injury at all. By the time the day is half over I feel 100% Wow. I’d no idea the eye could heal so fast. The only change I ever notice, in fact, is a much pronounced interest in eye protection.

Because, as mentioned before, the patina room could get beastly hot, I got in the habit of coming to work around 4am and leaving at lunch, if my work load permitted it. It was a great schedule. Not only was I guaranteed a longer stretch of comfortable temperatures, I could also end up with three to four hours of uninterrupted work. Well, most of the time, anyway. The problem is, I wasn’t the only early riser. It wasn’t that unusual for a few others to come in for a head start on a job or to work on their own projects, though I was usually the only person nuts enough to show up at 4am.

Because, as mentioned before, the patina room could get beastly hot, I got in the habit of coming to work around 4am and leaving at lunch, if my work load permitted it. It was a great schedule. Not only was I guaranteed a longer stretch of comfortable temperatures, I could also end up with three to four hours of uninterrupted work. Well, most of the time, anyway. The problem is, I wasn’t the only early riser. It wasn’t that unusual for a few others to come in for a head start on a job or to work on their own projects, though I was usually the only person nuts enough to show up at 4am.

One particular morning, I was joined in the patina room by a metal worker – I’ll call him Larry – who was in early to finish up one of his own pieces. After asking if it was okay to use one of the stations – “sure, have at it” – I go back to work, only to have my torch sputter out – *sigh.* I grab the tank wrench off the pegboard, remove my torch hose with it, roll the empty tank outside, roll a new tank in, hand crank on the torch, and Larry asks for some advice. So, I grab my coffee cup and head over to see what he needs.

While we talk, I empty my coffee cup so, finished here, I make my way up to the break-room for some fresh joe and am waylaid by another early riser from the shell department. We bullshit a bit as we pour and season our mud, then bid each other good day and I head back to patina. Enroute, I run into a welder who is in early and we joke around for a minute or two. So much for productivity.

Finally getting back to my station, I open up the tank valve, spark my torch, and begin heating the piece on my stand. A couple of minutes later, I turn to grab my brush and – WHOOMPH! – my torch ignites the propane leaking out around the hand-tightened-only hose fitting.

Finally getting back to my station, I open up the tank valve, spark my torch, and begin heating the piece on my stand. A couple of minutes later, I turn to grab my brush and – WHOOMPH! – my torch ignites the propane leaking out around the hand-tightened-only hose fitting.

Oh, well. That’s exciting.

I try to reach down and shut it off but the heat from the jet of flame is too much. I immediately cast about my bench for my heavy leather gloves. All I need do is shut off the valve and all will be well. The problem is, I am a little unnerved by the roaring flame. I can only find one glove and am using it like an oven mitt, rather than a glove, to turn the tank off. The valve handle on top of the tank is already super hot and is sticking in the open position. It needs one, good, firm crank to get going, so I kick at it with my leather-clad heel, achieving my goal but also incidentally spinning the tank so that, now, the foot-long jet of blueish-white flame is toasting the metal of the chemical-cabinet doors. Awesome. Well, at least I managed to loosen up the valve! The heat is intense, though, so I am only able to crank it closed with ginger little stabs – and that’s when Larry screams.

“AIIIIGH! OH, MY GOD! GET THE FUCK OUTTA HERE! IT’S GONNA BLOW!” And banging through the door he goes, screaming out onto the metal floor, hands held high in the air just like a cartoon character.

“AIIIIGH! OH, MY GOD! GET THE FUCK OUTTA HERE! IT’S GONNA BLOW!” And banging through the door he goes, screaming out onto the metal floor, hands held high in the air just like a cartoon character.

Now, I know that the pressure of the tank is not about to let the flame inside it, that there is no fear of explosion. I know that all I need to do is to close that valve but something about a man screaming in complete and utter abandonment to his fear triggers in me similar reaction so, hair on my neck fully erect, I abandon the only real solution to dash like a ninny through the back door of the patina room and out into the parking lot.

After about twenty yards, I turn back and see through the windows that my corner of the patina room is now engulfed in smoke. The welder I was jokeing with earlier strides into the room, takes a big breath, and marches over to the tank, his heavy gloved hands held out before him. Seconds later, the fire goes out.

Well, phew. Glad that’s over. Boy, do I feel foolish.

Other employees have arrived at work now and they’re congregating in and around the patina department to be near the excitement. I explain what happened to the metal-floor manager and he’s mostly amused by the story – only, it’s not over: we hear sirens. Larry’s called the fire department!

Other employees have arrived at work now and they’re congregating in and around the patina department to be near the excitement. I explain what happened to the metal-floor manager and he’s mostly amused by the story – only, it’s not over: we hear sirens. Larry’s called the fire department!

The fire department is not amused at all. They seem amazed at our operation: “What the heck are all these chemicals doing here next to where you’re heating up a bunny? Why would you want to make the metal bunny hot with a propane torch in the first place. And then put chemicals on it?!? I think you must need a special permit for this kind of thing. Do you have one? Have you applied for one? I need to talk to my supervisor about this. I’m not sure what you’re doing is legal – I know for sure it isn’t smart! Until that time, no one, and I mean absolutely NO ONE, is allowed to use flame in this room! Have I made myself clear? You’re looking at some fines, for sure.”

Oh, man. I think the metal-floor manager liked me better when I was sending him unlabeled monument panels from wax sprue …

In the end, things were cleared up. The fire department learned that there was this thing called “patina” that LOTS of people and businesses were doing around town, all of them potentially hazardous – and yet no one, until Larry and I, had managed to stir up any real excitement with it. They made us move our chemical cabinet and let us get back to work. I was given some stern eyebrows and Larry was let go.

“AIIIIGH!”

Despite the valiant efforts of those of us who remained on staff, we lost too many clients to be viable, and the place was sold to an even worse manager/owner. Luckily (?), around the same time, my wife became the recipient of a couple of trust funds (the flipside being that she also lost the singular most important person in her life, after her own child, in sacrifice for these trust funds – so it was a mixed blessing at best) and I was able to flee the sinking ship, myself.

Despite the valiant efforts of those of us who remained on staff, we lost too many clients to be viable, and the place was sold to an even worse manager/owner. Luckily (?), around the same time, my wife became the recipient of a couple of trust funds (the flipside being that she also lost the singular most important person in her life, after her own child, in sacrifice for these trust funds – so it was a mixed blessing at best) and I was able to flee the sinking ship, myself.

The problem was, I was nowhere near done with casting and finishing my own work – I had only just begun! While I wasn’t happy with all aspects of my job, what I liked I *loved,* and the opportunity to cast so cheaply, when the alternative was to not be able to afford it at all.

Moving from the sprue department to the patina department and away from ideas about wax stalled a lot of my projects, most notably “Narcissus Gone Awry” and “Athos.” On one of the last days I was part of the crew, I took in the bigger pieces and chunks of unused wax I had at home and put them one by one into the big vat in the wax department. We were moving from Colorado to Washington and I knew something like the unfinished “Naricussus” wax was unlikely to survive the move. I can still see the leg and head of it slowly sinking back into liquid form in the wax vat. It was fascinating to watch but the memory kills me, now. At the time I had illusions that, with connections in the industry, I’d be able to finish it, someday. I no longer have such illusions. I also left many waxes behind – payments in trade for work done by artist friends – left behind with assurances that friends in the industry who owed me favors would get them run through the process, at least through metal chase.

I never saw any of it.

Had I continued to work in the field, I have no doubt that there would be at least one, full version of “Narcissus Gone Awry” out there, somewhere – though *I’d* probably be dead or mentally fried from solvents and patina chemicals by now, too. As it is, I never even ended up with one of the “Narcissus” heads in metal. All I have is the little, digital photo you see above of the one my friend owns and the mold, which lies slowly rotting in a dark corner of my garage with a few others.

Had I continued to work in the field, I have no doubt that there would be at least one, full version of “Narcissus Gone Awry” out there, somewhere – though *I’d* probably be dead or mentally fried from solvents and patina chemicals by now, too. As it is, I never even ended up with one of the “Narcissus” heads in metal. All I have is the little, digital photo you see above of the one my friend owns and the mold, which lies slowly rotting in a dark corner of my garage with a few others.

Regrets, I’ve had a few …

In early spring of this year I traveled back to Colorado and, during the visit, ended up in a chapel to attend a high-school acquaintance’s funeral.

As we walked in, I noticed a large, bronze relief of a tree in the vestibule alcove. The leaves of the tree had names inscribed in them and were buffed to a high polish, the rest of the piece was finished in a french brown.

It took me a minute but I soon realized I had worked on the piece when it passed through the foundry.

I am aware of other pieces of still-public art that I had a hand in producing while at the foundry but this was the first time I’d run across a larger, one-of-a-kind piece in such a setting and, despite the fact that the weld lines were painfully obvious to me, I felt a surge of something like pride but also, strangely, of kinship. It was like meeting an old friend.

My time at the foundry was an important and amazing one. As insane, hot, hard, and mind numbing as the work could be, as annoying and downright hostile as the clients, management, and even some of my co-workers could be, as painfully, insultingly, bad as some of the “art” was that passed through our process, it was at this job where I learned I was capable with my hands. That I could make art as I saw it, for me if for no one else, without shame. Further, it remains one of the only times I have ever been a part of a group where I felt I truly fit in.

Sure, there were people who disliked me – or I them. There were jerks who made everyone’s day hard. People didn’t always get along with each other, and maybe one person’s concept of art wasn’t another’s – but the fact that you wanted to focus on the creative arts, had to do it; to eat it, breathe it, dream it; to produce and follow your own tune or go mad with depression – that was completely accepted. It was the rest of the world that had it wrong; the rest of the world that was weird.

God, I miss that feeling.

[…] continued … […]

God, I miss (some of) those weirdos.

Indeed! 🙂

[…] experience as a patineur has me wondering if I can’t do some kind of a cold patina on the things. What can I use to […]