(continued from: A Flood of Memories – Part 2 The Big Thompson Flood of 1976)

The river changed for me after the flood and, to this day, it is not the one I remember from my early childhood. The river we ice-skated on in the winter and that I caught my first fish from, on a piece of black thread with a rusty, found hook is long gone. A hazy but persistent memory that continues to define a very distinct and distant period of my life.

Floods update the shape and course of the rivers they spring from. The rushing water carves new beds from old banks, uproots foliage, rolls boulders, and deposits new layers of mud and sand where before, perhaps, there was none. Floods remove old landmarks and create new ones. Floods destroy human built landmarks and redefine how and where it is wise to place them.

As my immediate neighborhood had little to no structures within the floodwater’s reach, I mainly remember the flood’s effect on the river itself. The banks and immediate lowland around the Big T was pale and raw looking from where the high waters had torn up the landscape. Instead of the rich green of grass and shrubs or dark brown of fertile mud it was all tans and off-whites and pale pinks and dirty yellows. There were long scratches in the earth, as if the flood had claws; gouges scattered with out-of-place rocks, piles of trees stripped of bark, and everywhere an intermingling of indefinable metal, plastic, and worked wood.

Worst of all was the silt.

Silt is a term for a type of sediment, usually composed of tiny grains of crushed quartz and feldpsar, with a consistency somewhere between that of sand and clay. Silt is heavy enough to suck off a boot if you become mired in it, yet fine enough to be easily suspended in a flow of water. Silt is naturally occurring and often an important part of maintaining rich soils, such as along the Nile. In other cases, as from construction or our flood, an excess shock of silt can choke a river and its inhabitants.

For years after the flood, the Big T was clogged with this thick sediment, first from the flood and then the cleanup and reconstruction efforts. Even though they dredged and removed much of it, the mark of the silt is still there, with islands and sandbars where before there was not but deep water. The fish population of the canyon and immediate distributaries was almost entirely destroyed by the toxins and silt resulting from the flood and its aftermath.

Before the disaster, playing around in the river was a thoughtless pastime but after, it felt dirty and unsafe to me. Some of this sense was the effect of my mother’s warnings about rusty metal and other sharp flotsam deposited by the flood waters but the rest was caused by the generally rancid smell that pervaded much of the river and its debris laden banks. Further, as not everyone – or all of everyone – lost in the flood was ever found, including a classmate at my elementary school, there was always the fear of stumbling upon something even worse than a sharp bit of rusted metal. For years after, any bone-like material I found alongside the Big T’s flow was disturbing and suspect.

Another bit of fallout from the flood was stardom for the area. Suddenly, after decades of being largely forgotten, the falls at Big Dam were an attraction again; a designation the landmark was ill-suited to handle.

Prior to the flood, our little valley seemed like a private haven. Sure, there were the occasional, summer tourists trickling through but never enough to remark on. Afterwards, people were suddenly interested in the course of the river and, too soon thereafter, the falls.

Initially this just meant lookie-loos peering over the edge and hoping to see some hint of the flood’s destruction but, the following summers, with the bulk of the debris cleaned up and reconstruction well on its way, the falls and immediate valley below became a hangout for the young, the drunk, and the scantily clad.

Thereafter, sightings of the sheriff or an ambulance became a regular occurrence as some jackass or another got out of control with their partying or hurt themselves with a blind leap from the cliffs of the falls to the ever changing depths of the silt laden pools below.

One drunken Fudd actually went over the falls on an inner tube, somehow only breaking an arm. He was fished out but his tube remained trapped behind the falls for hours, the water hitting it sounding like the pops of a handgun as it bobbed in the wash. The sheriff took pity on the neighborhood and there was one last pop when he shot the thing from one of the flume’s observation decks.

Despite attempts to suppress such activity, the falls remained a popular hangout and, slowly but surely, more and more controls were placed on the area: signs, fences, regulations, prohibitions. By the time I was a teen, it was not uncommon to have my clamberings interrupted by a county officer. They would release me once they learned I was of the neighborhood, if less easily so with each passing year.

Now the area is regularly patrolled and the neighborhood watches all goings on through drawn drapes. You can hardly see the view I once took for granted. I understand that the few ruined it for the many and protecting the property is necessary but it saddens me greatly to have what I always thought of as the best part of my childhood’s playground not just inaccessible but partially obscured by an 8 foot tall, ugly, brown fence.

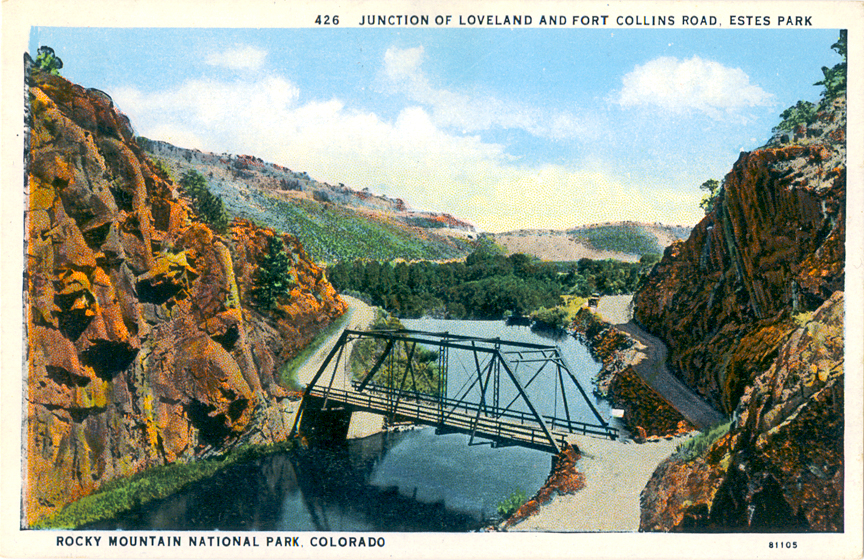

Replacing the bridge up river from the falls was a key element to bringing our neighborhood into the new normal.

Originally built to serve as a connection between the canyon and the more populous city of Fort Collins, the now lost bridge had been built at such an angle as to make it nigh impossible for longer vehicles coming off of our road to make the corner. Because of this, for the first couple of years of school, I was driven to a friend’s house one foothill over to catch the school bus; its length prohibited crossing and turning around.

When planning a replacement bridge, the decision was to lose this angle – a major improvement that all applauded.

In order to make this proposed change work, some of the cliff face on our side of the river needed to be blasted away to allow for “swing” room: that little, initial turn opposite the intended direction that drivers make when taking a sharp corner, especially in longer vehicles.

Most of the this blasting occurred during the workweek. The neighborhood was warned of the blasting schedule at least 24 hours beforehand and the approaching roads were blocked off. My brother and I resented being in school for the blasts and checked out the progress nightly on our bikes. It was fascinating to see how the crew drilled straight into the stone of the cliff face to place the charges. Sometimes the cliff would shear away cleanly, other times it would crumble, leaving precarious clumps of shattered stone hanging above the roadway. We would eye these with interest as we passed beneath them: don’t sneeze! Much of the rock blasted free was recovered and worked into the project at hand.

We had friends who lived across the river, on top of the cliff above the construction site. Theirs was the only house in view of the work being done and we envied them their vantage point even though the eldest of the two boys, a fellow in my brother’s grade, had been laid up in bed for months with a badly broken leg.

One day the blasting team used a bit too much dynamite and the resulting spray of rock peppered our friend’s home with stones ranging in size from tiny pebbles to rocks the size of birthday cakes. The little ones just stuck in the siding or, having shot through the glass of the slider, embedded itself into the textured sheetrock of an interior wall. One of the birthday-cake sized rocks tore through the roof of the house and landed in the bed of my brother’s laid-up schoolmate. Luckily, this was his first day back at school, or he’d most likely have been killed. As it was, he got a nice skylight out of it, paid for by the county …

The new bridge was a success. Not only was the old, restrictive angle of the thing gone but the sense of strength, durability, and safety embodied in the modern, solid concrete span well outweighed the antique charm of the old, wooden arch with its creakings and and only partially covered deck. My brother and I relished playing beneath the new bridge and leaving long streaks of black on it with our pedal-brake bikes. Further, we could now catch the bus in front of our own house. I couldn’t even picture the old bridge in my head any more, even though I missed its character.

For those of us not directly injured by the flood, the effects of the disaster were more abstract. This was especially true for those of us who were kids at the time. I never fully grasped the immensity of the pain and horror of that night until I sat down here, nearly forty years later, to write about it.

Instead of being frightened or traumatized by the disaster and its aftermath, my brother and I were fascinated. We listened to the sad and gory tales of my aunt and others with eager ears. We poured over the pictures of the destruction in a book my parents got entitled “The Big Thompson Disaster”, in hopes of seeing a body. We simply didn’t get it. To us, it was just a big adventure, like a movie, that we wanted to make more real. I still resented the fact that I’d not been awakened to see the destruction first hand.

As usual, the creative mind of my brother found a solution for this mutual, macabre desire to know more about the nature of water’s power.

The three acres we lived on held not just a house and separate, two-car garage but also a third, L-shaped building. Initially unfinished with open walls and a dirt floor, my dad poured a concrete pad and entry walk for the building, wired it for electricity, rocked the walls and built sturdy counters onto them, transforming this dim, plaster and lathe garage-cum-shed into a well-lit, clean and serviceable wood shop.

Built into a hill, the building’s south side sits up to its window sills in earth and it is here, in the corner of the “L” that my brother and I have our sandbox.

While I dig primitive caves out of mud and carefully exhume recently buried plastic dinosaurs, my brother, a natural engineer, constructs believable tableaus from the dirt. The year after the flood, it is he who has the idea to set up all our favorite toys in the sandbox and then flood it to see the results.

The idea is off the cuff and little more is done than the gathering of a few toys and the garden hose. We perform a quick setup with little rhyme or reason – my 12” G.I. Joe doll standing less than a foot away from a plastic HO scale building – then open the tap on the hose.

Watching the water levels rise. Seeing it spill over into lower areas, how it erodes the earth, buries things in sediment, carries them from one spot to another, is revelatory. When something is unsatisfactorily affected, we move it to a different area with more potential for violent change. Fascinating.

We leave the hose on until the last bit of the sandbox’s dirt disappears beneath our flood’s muddy surface. Toys poke up from the mire here and there, stranded. As the water levels recede into the dirt, the scene is even more reminiscent of the flood: cars, buildings – and now bodies – partially buried in muck and slowly revealed as the flood waters drain away.

As the water sinks into the earth, it’s natural inclination, of course, is to flow downhill. Downhill is my father’s shop, which has no real foundation. Cleaning up our water-logged, mud-caked toys, one of us catches a glimpse through the windows and notices that the shop floor below us is flooded.

Oh, shit.

For his children, my father is none too easy to get along with during even the happiest of times. One way to ensure unhappy times is to not properly replace a tool in his shop. Or to use it without asking. Or to even be in his shop without permission. Now, here we are, looking into my father’s sanctuary, flooded with our water.

I repeat: Oh, shit.

My brother, already feeling ‘The Stick’ on the backs of his legs, teaches me how to syphon with a hose and I attempt to drain the remaining water out of the sandbox and into the lilac bushes that line our driveway. Meanwhile, my brother has sneaked into my father’s locked shop and is trying to sweep up all evidence of our transgression. Finished, he even goes so far as to try to redistribute a believable layer of sawdust around the shop floor to replace that which was sopped up.

When my father comes home, it takes him less than five minutes to detect what has happened and he calls us over for an explanation. The truth is extracted, along with a pound of flesh for punishment, and an admonition: no more water in the sandbox.

The following summer, our flood is even better.

My brother spends a day and a half turning our lumpy, gritty, toy strewn sandbox into a believable, Matchbox car scale landscape, complete with buildings, roads, waterways, and little scenes of people and animals. Everything is in proper scale, strategically placed here and there throughout. I’m allowed to add a few favorite cars or such but we both agree that he knows what he’s doing and I’d only mess things up. When he is finished, we carefully fill the large reservoir he’s constructed in one corner of the sandbox with the garden hose and await the destruction.

None comes. Instead, his thick, level, packed-earth dam holds and we are further drawn into the fantasy. Using a stick, my brother challenges a minute portion of the dam’s spillway and our disaster begins. Water trickles out around the hole, flowing down the riverbed carved into our scene, gently now but growing as the hole in the dam widens, the earth crumbling into it.

Just below the dam, a truck hauls a trailer across a little, wooden bridge. Oh, mercy but they appear to be stalled halfway across. The abutments begin to erode as the flood strengthens and now the truck, trailer, and bridge tumble into the flow. Similar scenes play out the as the current from the hose in the reservoir wreaks its havoc. I am particularly taken by slow, inevitable erosion and the carving out from under of banks.

Instead of filling the sandbox as before, we allow a flood that ebbs as the real one did in ’76. Then we wait for the water’s recession to reveal the leavings. The results are fantastic and almost disturbing in their believability. We pour over the scene for some time with a forensic interest, prying certain objects out of the muck and remarking to each other over any particularly ironic or realistic looking result.

The problem is, we’ve somehow managed to forget the effect the flooding will have on our father’s shop. While our facsimile of the disaster is more controlled this time around, we play longer with the water and, thus, end up flooding the shop worse than before. Again a frantic cleanup is undertaken and, again, all for naught. This time the punishment is more severe than a talking to and we swear on our souls to never again play with water in the sandbox.

The next summer, we are far more careful with the amount of water used and are never caught again though, in truth, we probably only played “Flood!” for a couple of more summers.

Beyond the hilarity of our foolishness with my father’s shop and my brother’s ingenuity and artistry in making our little floods so fascinating, I cannot help but wonder if this annual reenactment was more than just the morbid curiosity of a couple of boys. Were we just playing or were we instructing ourselves? Pretending to be a kind of god with the floods gave a sense of control over forces similar to the ones we were witness to and helpless in the face of that summer of 1976.

I’ve spent my life thinking that the flood had very little emotional effect on me and this has occasionally been bothersome: am I some kind of sociopath? Returning to that summer in my mind and digging into the facts for this memoir has had far greater impact on me and I know now that it was my age and inexperience that had me less able to empathize. I now grasp the magnitude of what happened and how it must have been for those more intimately affected. I am adult, now, have children of my own, and no longer find the concept of such destruction mysterious, exciting, or attractive. I have friends and acquaintances who could tell much more harrowing tales of that night than I, if they wanted. For them, it was always a horrible event and never just an adventure. Still, looking at those successive years of reenactment in our sandbox, reflecting back on that night and what was lost: the illusion of permanence; I remain both humbled and thankful for the experience.

Part 1: A Flood of Memories – Part 1 – The Big Thompson Flood of 1976

Part 2: A Flood of Memories – Part 2 – The Big Thompson Flood of 1976

[…] Continued: A Flood of Memories – Part 3 The Big Thompson Flood of 1976 […]